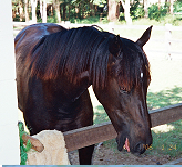

Lesion when it was first noticed

My son, Tully owns “Honey”, a 10-year-old 9hh mini-pony he drives in harness. Tully was awarded the 2019 Junior Driver of the Year by the Australian Carriage Driving Society.

The February 2020 rains brought grass back to our farm in Northern NSW, and filled the back swamp that had been bone dry. On the 11 March I noticed a small, weeping sore on Honey’s offside pastern. I knew it was Pythium Insidiosum. Often, the initial lesion is mistaken for pastern dermatitis, a small cut, proud-flesh or many other common, skin conditions. Pythium is confined to tropical and subtropical regions, with most infections occurring when temperatures are between 30C and 40C. From past experience with this disease I knew it to be true to its name, it is insidious. Think water borne mould, on steroids with a cloak of immunological invisibility.

To understand what Honey was facing, I need to give a quick biology lesson. Pythium insidiosum is an oomycete, a “water mold”, having fungal characteristics but not a true fungus. Oomycetes are found in standing or stagnant water, hence the common name “swamp cancer” for Pythium infections. Pythium usually lives in aquatic vegetation, but at certain stages it develops zoospores that have motile flagella. These swimming zoospores seek out vegetation, or if present, horse hair or skin. The zoospore cannot pierce skin but finds an entry point of broken skin, an insect bite is sufficient, and enters the animal. Once inside, it sheds its flagella and starts colonizing the flesh by sending out hyphae (think microscopic roots), which tear the flesh apart, starting a cascade of biological reactions. The body identifies Pythium as an allergen, not a killer, and starts a normal allergic response resulting in itching and exudate. This is the “Th2” immune response. However, Pythium is smart (if an oomycete can be smart), and makes the body create a concrete like substance around the hyphae termed “kunkers”. Even though Pythium infects dogs, cats and even humans, kunkers are only found in equine pythiosis. Unfortunately, the Th2 response is the wrong response. The body needs to recognize the threat and send its “Th1” immune response to kill it, however, the kunkers cloak the hyphae and the body stays locked in its ineffective Th2 immune response. What results is a weeping, mushy wound with microabcesses and draining tracts, growing rapidly every day, with an itch so severe it causes self-mutilation.

I spent the next day calling up vets to get an appointment so we could start treatment. Time is precious; the best prognosis requires treatment within 20 days of infection. The vets returned my calls; one wasn’t interested in treating Honey, (due to such poor prognosis), another was prepared to take her on but did not have the facilities to treat a horse. My usual vet, Dr Oliver Liyou specialises in equine dentistry and reproduction. As a rule, he doesn’t do emergency work, but as a long-standing client, he agreed to see Honey at 8am the next day for a diagnosis, but not necessarily for ongoing treatment. That evening I noticed a kunker and the lesion had spread, any hope I was dealing with a simple infection was gone.

At the appointment, the diagnosis was obvious. Dr Oliver and I both knew it was Pythium; treatment would be expensive and likely futile. Dr Oliver and I had been down this road a decade earlier, with my stockhorse, Tommy (euthanised after unsuccessful treatment). Two things were different now; I had a disposable income and new treatment options existed; both surgical and pharmacological. We formed a war plan, essentially throwing every scientific treatment that had ever shown experimental success against this organism. Excision of the lesion, IV treatment with sodium iodide, topical treatment with DSMO and Immaverol, and a course of painful immunotherapy injections. Dr. Oliver knew an excellent equine surgeon, Dr David Ahearn, skilled in electrocautery surgery, practicing in Queensland that day. So, we loaded Honey and the children up and drove north, whilst Dr Oliver tracked Dr David down and made our appointment. He would ring us en-route and tell us which clinic Dr David was at. Five hours of driving (and some pit stops for all of us) we arrived, handed Honey over to the vet nurse and found a nearby caravan park for us and the kids to camp in. Honey stayed in $100 per night comfort and we camped in the horse float for $35 a night! We got news after 9pm that she had gotten through surgery. The infected tissue had been excised right back to the digital flexor tendon to attempt a clear margin. The next morning we drove back home with Honey looking happy and healthy. We were to apply topical Immaverol and DSMO every three days with her bandage change, and she needed two sodium iodide IVs in the first fortnight. She also got sodium iodide salt in her feed twice a day.

Distal limb perfusion at Dr Oliver’s surgery

On 16 March, Honey had her first dressing change and an IV of sodium iodide, an antifungal, which theoretically shouldn’t work (remember Pythium isn’t a fungus), but some studies found it effective. A commercially available immunotherapy vaccine was ordered through Dr Oliver, which we began on 18 March. Also, IV Amphotericin B had shown limited efficacy in treating Pythium (again it shouldn’t really), however, for it to reach a distal limb lesion via traditional IV, it must be at a concentration that could cause liver damage, and Amph.B is hideously expensive! However, a recent study had success administering it via regional limb perfusion, and adding DSMO carried it across membranes deep into the tissue. On 19 March, Dr Oliver sourced the Amphotericin B from the nearby Regional Base Hospital, (not covered under Medicare!) and perfused the hoof with the two medications. Two kunkers were evident.

By 22 March one kunker was present. Kunkers are indicative of active pythiosis, however, it was hoped the immunotherapy would stop kunkers in the first week. Optimistically there was a large lump at Honey’s injection site. The research indicated that horses with a moderate to large reaction had a better prognosis. These injections were the most painful part of the treatment. The purpose of the immunotherapy is to introduce processed Pythium into the horse’s system without its biological cloaking device. The body can then recognise the Pythium as a lethal parasite and trigger the appropriate Th1 immune response replacing the (useless) Th2 response.

Lesion 3 days post surgery

Lesion 6 days post surgery

Lesion 12 days post surgery

We did see a reduction in kunkers. On 25th March, the second vaccine injection was given, it was 6 days post Amph. B IV, 12 days’ post-surgery and 3 days without kunkers! Unfortunately, on 29 March, a kunker was visible. The Pythium had spread to the other heel bulb. She had also started to bite her heel due to the Pythium itch. Surgical removal of Pythium is a bit like cutting mould off cheese, you think you’ve got it all, you’ve cut a good 1cm off the block, past the mould, but it returns unless all the hyphae are removed.

What to do next? Dr Oliver contacted Dr David again, and he proposed more precise laser surgery. By now, the Queensland border was closed without a permit, but living near the border, we got a permit to obtain essential services. Only Scott, my husband made the trip this time, leaving at 4am, Honey had surgery, and returned home that evening.

Dr David was optimistic, getting a good margin and the infection was not as advanced as it was previously. Honey’s hoof was in a fibreglass cast for 3 weeks, to be removed on 24 April. There was nothing more to do. I tried not to have any expectations, however, she never became lame, there was no putrid smell, (and you never forget Pythiosis smell) and no exudate seeping up the internal bandaging. To me, all good signs but Pythium can’t be second guessed. The day before Honey’s final appointment, I had to prepare Tully emotionally that Honey may be euthanised, yet not crushing his hope that she would be healed. Tully decided to spend some time with her, realising it may be their last evening together.

Casted hoof

Friday 24 April arrived to take the cast off. Tully gave Honey a pat and said he would see her soon. Tully thought it be best not to go, and I assured him I would be with her feeding her carrots right until the end if it came to that. If Pythium was still there it wouldn’t be a pleasant sight; we would load Honey back onto the horse float and euthanise her. I had prepacked a tarp to walk her on to, which we could use to slide her out afterwards, and a pretty blanket to cover her up for her final trip home so if Tully saw her, it would be an image of a peaceful passing. I had a backhoe waiting at home ready to dig her grave. I wanted it to go smoothly for Tully’s sake.

It took about 45 minutes to remove the cast. Honey’s harness training stood her in good stead, she didn’t need a sedative and stood immobile whilst knives cut through outer bandaging, and a reciprocating saw cut through the fibreglass, and lastly, Dr Oliver and Scott used brute strength and cold chisels to prise the cast off her tiny hoof. The moment had arrived, the packing was removed. We were looking at a dry, Pythium free pastern. Dr Oliver was ecstatic, the vet nurse overjoyed, and Scott was stoically pleased. I exhaled and walked away, overwhelmed with relief. I Facetimed Tully and he was thrilled, but not surprised. In spite of my best parenting to prepare him for the worst, I think he humoured my pessimism, and substituted optimistic thoughts instead.

Honey’ now fully recovered

A year on Honey is in the paddock grazing happily. She is back in harness and you wouldn’t know how death defying her experience actually was. I will leave you with my take home message of equine Pythiosis:

1. In subtropical and tropical areas, keep horses out of areas with standing water. Tommy had been in the paddock for 10 years, Honey had been in the same paddock once. If Pythium is in the water, it’s just luck of the draw.

2. If your horse has had access to standing water in warmer weather, check for lesions. The less time from infection until treatment the greater the chance of a cure.

3. Local knowledge is great, but take it with a grain of salt when they say they cured “swamp cancer” with bush remedies (bluestone etc). “Swamp cancer” is a local name for a lot of different diseases, which may or may not be Pythium Insidiosum. Get a vet to diagnose and ask if they have considered Pythiosis.

4. Be realistic about your financial, physical and emotional resources. You will need good amounts of all three, and even then, you may not get a cure. If Pythiosis is advanced, consider if the extent and duration of pain to the horse during treatment is justified by the chance of recovery.

5. You can see full pictures of Honey’s Pythiosis lesion and treatment at https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.10216618109513876&type=3

This article and accompanying images were kindly contributed by Heidi Naylor, a dedicated horse owner who hopes that sharing her knowledge and experience with this disease may help others.